The White Problem

Here is a fruit

For the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather

For the wind to suck

For the sun to rot

For a tree to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

”Strange Fruit”

Abel Meeropol

“Strange Fruit” was penned in 1937 by Jewish American writer, Abel Meeropol under his pseudonym, Lewis Allan. The poem was inspired by the photograph of the mob lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith on August 7th, 1930 in Marion, Indiana. Over 5,000 white people came to view the lynching of the black men, their bodies hang lifeless, their clothes look as if wild animals had seized upon them. The sight of the dead black bodies is an image that burns into the brain. However, our eyes should fixate on the white faces in the crowd. The photograph shows white spectators with smiles on their faces, pointing proudly at the brutalized, lifeless bodies. White women and children look on with gleeful satisfaction. We know this photo was later made into a postcard, that was the tradition.

However, what if the “strange and bitter crop” are the white people in the photograph? Both killers and enablers, who is this ‘strange and bitter crop’ of people that stomach the stench of dead human beings and bring their children to witness the act? What is the condition of their souls? What is wrong with a group of people who cannot see the humanity in others?

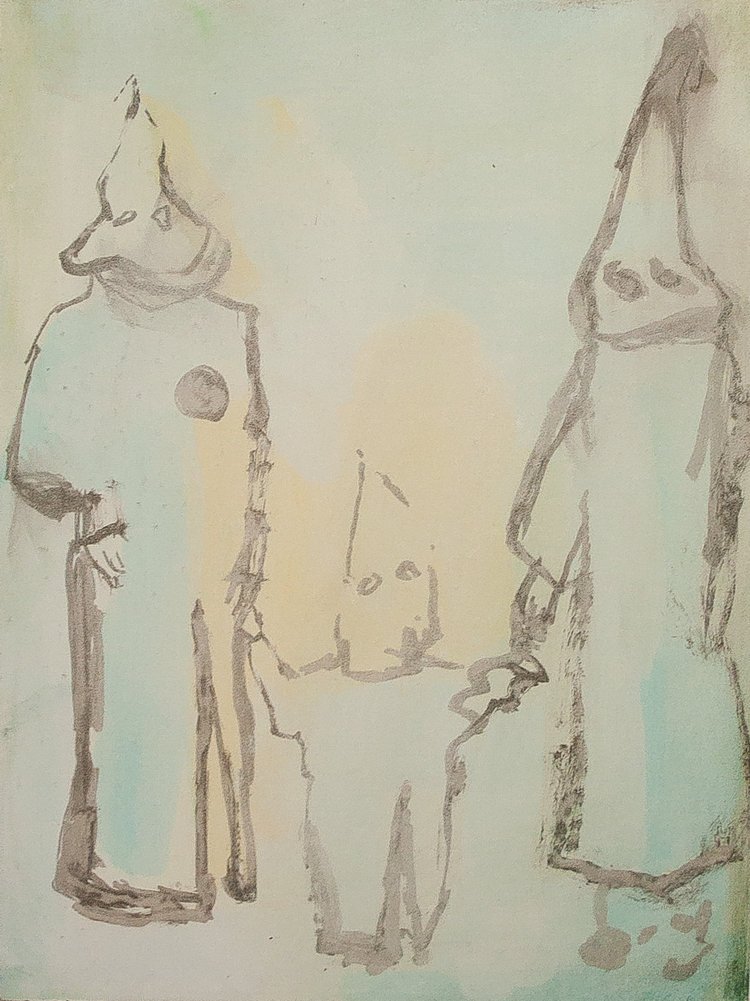

In Carla Repice’s exhibition,“The White Problem”, Repice pulls back the curtain of white racism and the physical, psychological and spiritual violence that it breeds. We see how racism and white violence severely corrupted the humanity of white people. Repice predominantly brings us into the space of children - where the foundation of these dehumanizing ideas are carefully planted and religiously watered. In the piece, “Lineage”, we see a white child standing with a gun, and with what appears to be the adult figures in their life hooded and hovering like ghosts. This is a rite of passage. The gun has been the tool of genocide and colonization in the history of white violence for centuries. These children, with guns, hands and targets over their hearts are raised to equate love for whiteness with hate for “the other.”

Repice presents schools and schooling as another tool of white supremacy and violence. Though the concept of white supremacy and the hate for “the other” may begin at home, it is metastasized in the system of schooling. Schools are a harbor of white intellectual, emotional and physical violence. It is here that white supremacy is consciously and unconsciously taught and practiced. In one piece, we see students standing in a line seeming to pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States. Repice makes us wonder if pledging allegiance to America is synonymous with pledging allegiance to the racism and violence that birthed the nation. We see students learning by rote which juxtaposes the learned racism and violence in the home. In other pieces, the viewer is forced to look into the eyes of children. One piece features a white child with a red mark covering the majority of their face. The legacy of white violence has marked them. The viewer must look directly into the eyes of two young black girls who are often overlooked in the discourse on the effect of racism on black children. In our school system, black girls are seven times more likely to be suspended than white girls. In the justice system, black girls are the fastest growing demographic in terms of arrest and incarceration.

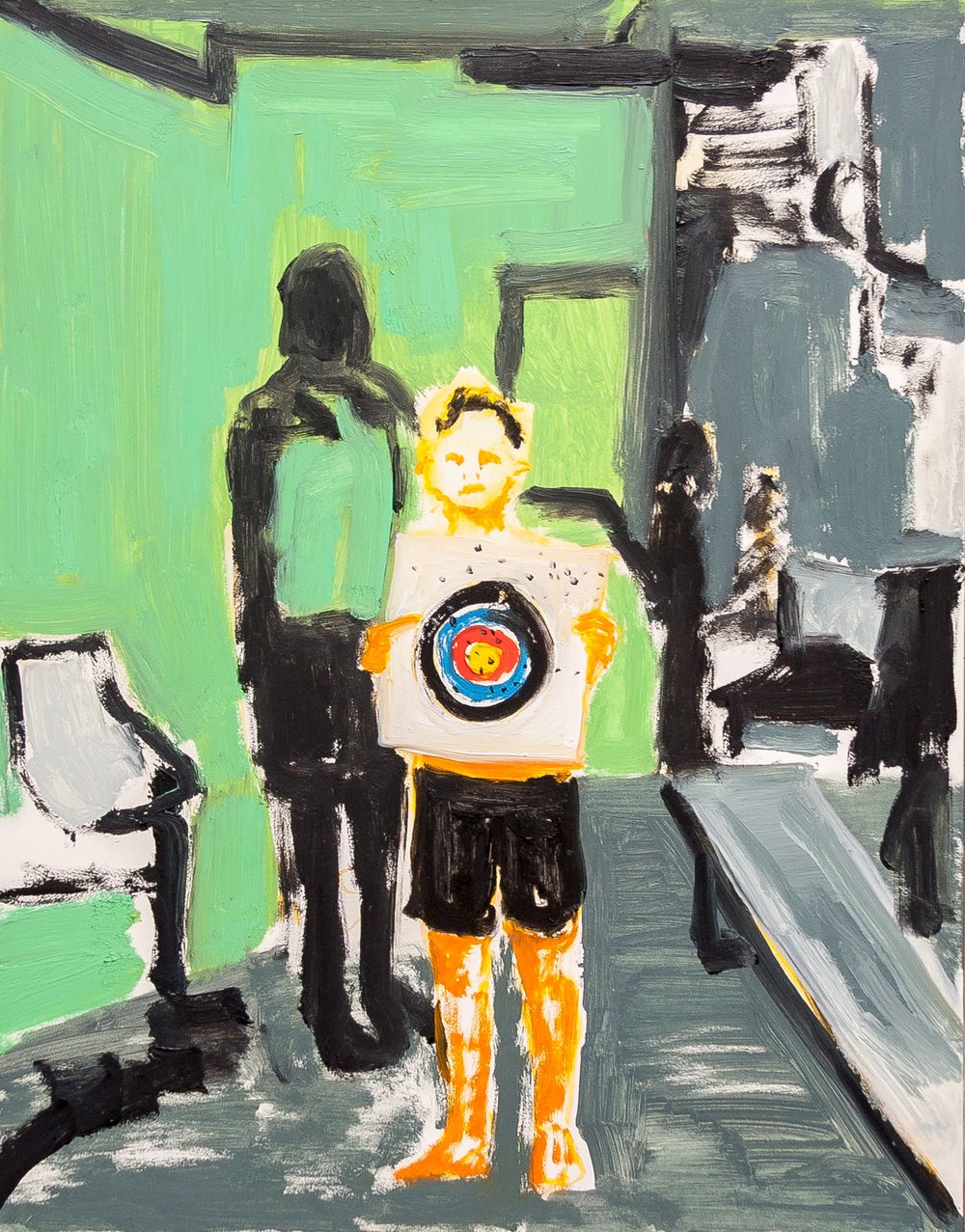

Repice makes powerful use of the target motif throughout. We see white children holding targets. Both the predator and the prey. Torchbearers of the legacy of violence handed down to them by their forefathers and foremothers. School shootings are on the rise. White people feign confusion and perform ignorance as to where this anger has come from. As Malcolm X famously and prophetically stated in 1963 after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, “the chickens have come home to roost”. The violence that has been taught, ignored and glorified has now returned to the doorstep of white america. In present day, the chickens are coming home to roost in the form of a rogue president that the grandmothers and mothers of white america gave the keys of the highest office of the land to rule. The chickens are coming home to roost as white america is getting some taste of the violence and the insidious hypocrisy that black and brown people have been navigating for centuries.

In the end, Repice’s exhibition poses the question that African American activist, Pan-Africanist and scholar, W.E.B Dubois posed back in 1903 in The Souls of Black Folk: Between me and the other world there is an ever unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. What does it feel like to be a problem?

—Robyne Walker Murphy, May 15, 2019